More Information

Submitted: November 25, 2025 | Approved: December 05, 2025 | Published: December 08, 2025

How to cite this article: Rataul RK, Shinh AS, Natt AS, Maheshwari K, Kaur S. Comparative Evaluation of Mechanical Performance among Fixed Orthodontic Retention Wires. J Clin Adv Dent. 2025; 9(1): 015-020. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jcad.1001051

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcad.1001051

Copyright license: © 2025 Rataul RK, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Mechanical properties; Tensile behavior; Modulus of elasticity; Fixed retainers; Multistranded wires

Comparative Evaluation of Mechanical Performance among Fixed Orthodontic Retention Wires

Ravneet Kaur Rataul1*, Amanish Singh Shinh2, Amanpreet Singh Natt3, Karan Maheshwari4 and Sharnjeet Kaur4

1Post Graduate Student, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Adesh Institute of Dental Sciences & Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India

2MDS Orthodontics, Principal & HOD, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Adesh Institute of Dental Sciences & Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India

3MDS Orthodontics, Professor, Department of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Adesh Institute of Dental Sciences & Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India

4MDS Orthodontics, Associate Professor, Department of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Adesh Institute of Dental Sciences & Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India

*Address for Correspondence: Ravneet Kaur Rataul, Post Graduate Student, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Adesh Institute of Dental Sciences & Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India, Email: [email protected]

Background: The biomechanical reliability of fixed orthodontic retainers is integral to achieving durable post-treatment stability. With a broad spectrum of multistranded stainless-steel wire designs available in contemporary orthodontics, a rigorous and evidence-based assessment of their mechanical performance is essential to guide clinical decision-making. This in vitro investigation provided a systematic and analytically robust evaluation of four clinically utilized retainer wire configurations, emphasizing tensile strength, yield strength, and modulus of elasticity—parameters that fundamentally determine structural integrity and long-term functional behavior.

Methods: Seventy-six multistranded stainless-steel wires were allocated into four groups (n = 19): Group 1 (7-stranded, 0.0175”), Group 2 (6-stranded, 0.0195”), Group 3 (6-stranded, 0.0175”), and Group 4 (5-stranded, 0.0175”). Each specimen underwent monotonic tensile loading using an Instron Universal Testing Machine (TEQIP-II) under standardized laboratory conditions. The resulting load–deflection curves were examined to determine the modulus of elasticity and yield strength. Intergroup statistical comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test, with significance established at p < 0.05.

Results: Significant intergroup differences were identified for all evaluated mechanical parameters. The 7-stranded 0.0175” wire (G&H) displayed the most advantageous mechanical profile, demonstrating the highest tensile capacity, increased yield strength, and superior stiffness. The 6-stranded 0.0175” (Optima) and the 6-stranded 0.0195” (OrthoClassic) wires exhibited intermediate performance, whereas the 5-stranded 0.0175” wire (Acti 5S) presented distinctly inferior biomechanical characteristics.

Conclusion: Within the limitations of an in vitro design, the 7-stranded 0.0175” configuration emerges as the most mechanically robust and clinically advantageous option for sustained orthodontic retention, while the 5-stranded 0.0175” wire demonstrates markedly reduced structural competence.

Orthodontic retention refers to preserving teeth in their most stable esthetic and functional positions once active orthodontic therapy has concluded [1]. Angle underscored the complexity of this phase, noting that retention often tests an orthodontist’s skill more than the treatment itself [2]. Despite successful alignment, teeth naturally tend to relapse toward their original positions due to residual periodontal fiber tension, muscular imbalances, and growth-related or age-related changes [3]. The precision of the final occlusion also influences long-term stability, as minor occlusal interferences can trigger unwanted post-treatment changes [4].

Effective retention aims to minimize these risks. Following debonding, teeth must be stabilized until the periodontal and supporting structures of the stomatognathic system adapt to their new positions [4]. Retainers therefore serve an essential role—not only in preventing relapse but also in limiting long-term positional changes. In selected cases, procedures such as interproximal reduction, overcorrection, fibrotomy, or removal of third molars may further enhance stability.

Retention protocols vary widely among patients, and in many instances, lifelong retention may be recommended. Retainers are broadly categorized as removable and fixed. Removable options include Hawley appliances and clear thermoformed retainers, while fixed retainers consist of orthodontic wire bonded to teeth using acid-etch composite. Fixed retainers have gained prominence due to their superior esthetics, independence from patient compliance, and suitability for long-term stabilization [5]. Consequently, bonded retainer wires form a discreet yet indispensable component of modern orthodontic practice.

These wires are manufactured in various materials, configurations, and diameters. Stainless steel was historically predominant [6], but advancements in biomaterials introduced nickel–titanium alloys and multistrand designs, offering enhanced flexibility and adaptation [7]. Multistrand wires—composed of three to seven coaxial or braided strands—provide diverse mechanical profiles tailored to different retention needs.

Despite their advantages, fixed retainers may fail through debonding, distortion, fracture, or unintended torque expression. Such failures are multifactorial and often related to inadequate wire adaptation, bonding errors, or insufficient mechanical strength of the wire [8]. Therefore, understanding the mechanical properties of these materials is essential. Key parameters such as Young’s modulus, yield strength, and ultimate tensile strength determine a wire’s stiffness, resilience, and resistance to deformation under functional loading. Although these characteristics remain concealed intraorally, they critically influence the longevity and reliability of retention systems [9].

Selecting the appropriate retainer wire is thus a pivotal clinical decision. An ideal wire must withstand occlusal forces, minimize unintended tooth movement, allow physiologic mobility, and maintain dimensional stability over time while ensuring firm adhesion to the tooth surface [10]. Given the wide range of available materials, evidence-based selection is essential to ensure predictable, long-term orthodontic stability.

The purpose of this study, therefore, is to evaluate and compare the tensile strength, yield strength, and modulus of elasticity of various types of fixed retention wires under a universal testing machine to demystify the mechanical properties of these wires and unlock their potential to serve as steadfast sentinels of orthodontic success.

Study site

The study was conducted in the Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Adesh Institute of Dental Sciences & Research, Bathinda.

Study sample

A total of 76 multistranded orthodontic retainer wires were evaluated. The specimens were categorized into four groups with 19 wires in each group, based on strand configuration and diameter. Group 1: 7-stranded wire (G&H, USA) – 0.0175″ (AISI 302 SS) (n = 19). Group 2: 6-stranded wire (Orthoclassic, USA) – 0.0195″ (AISI 304 SS) (n = 19), Group 3: 6-stranded wire (Optima, USA) – 0.0175″ (AISI 302 SS) (n = 19), Group 4: 5-stranded wire (Acti 4S, Luxembourg/Spain) – 0.0175″ (AISI 316L SS) (n = 19). Armamentarium used -Orthodontic retainer wires, Universal Testing Machine (TEQIP-II, India), and a custom jig assembly was fabricated to secure each specimen during testing (Table 1).

| Table 1: Summary of experimental groups and wire type. | ||

| Number of groups | Materials | Number of wires |

| GROUP 1 | 7 STRANDED RETAINER WIRE (0.0175”) | 19 |

| GROUP 2 | 6 STRANDED RETAINER WIRE (0.0195”) | 19 |

| GROUP 3 | 6 STRANDED RETAINER WIRE (0.0175”) | 19 |

| GROUP 4 | 5 STRANDED RETAINER WIRE (0.0175”) | 19 |

Universal testing machine

A universal Testing Machine (TEQIP-II, INDIA) was used to test the tensile Strength of retainer wires.

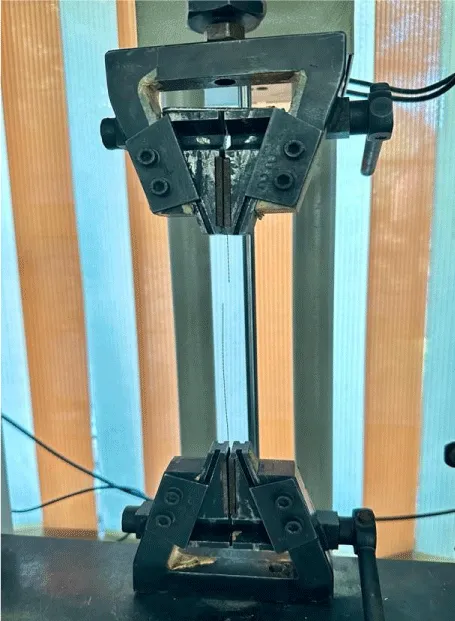

Custom-made assembly

A custom-made assembly consisted of upper and lower members, which were attached to the Universal Testing Machine. The wires were attached to the jig assembly by turning around the threaded screw and securing them with the help of a bolt.

Retainer wires were divided into four groups (n = 19 specimens per group).

Group 1 consisted of a 7-stranded stainless-steel retainer wire of diameter 0.0175″ (G&H Orthodontics, USA).

Group 2 consisted of a 6-stranded retainer wire of diameter 0.0195″ (ORTHOCLASSIC, McMinnville, USA).

Group 3 consisted of a 6-stranded retainer wire of diameter 0.0175″ (OPTIMA, USA). Group 4 consisted of a 5-stranded stainless-steel retainer wire of diameter 0.0175″ (Luxembourg, Spain).

Tensile testing was performed using a universal testing machine (Instron, TEQIP-II supported). A custom jig with upper and lower grips was fabricated to prevent slippage of the multistranded wires during loading. Straight 6-inch segments (80 mm) of wire from each group were secured between the grips, such that the entire 80 mm length acted as the gauge length (L₀) during tensile loading. A full-scale load cell of 1 kN was used, and the crosshead speed was maintained at 1 mm/min until fracture. During testing, the machine software continuously recorded load (N) and elongation (mm), generating a load–elongation curve for each specimen. Engineering tensile stress (σ) was calculated by dividing the instantaneous load by the initial cross-sectional area of the wire (A₀), derived from the manufacturer-specified diameters:

σ (MPa) = Load (N) / A₀ (mm²)

Engineering strain (ε) was computed as the ratio of elongation (ΔL) to the original gauge length:

ε = ΔL / L₀

Using the stress–strain data, a tensile stress–strain curve was constructed for each specimen. The Young’s modulus was determined from the slope of the linear elastic region using linear regression. The yield strength was obtained using the 0.2% offset method, and the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) was defined as the maximum stress before fracture.

This procedure was repeated for all 76 specimens across the four groups. The stress–strain behavior was used to derive group-wise mean values for tensile strength, yield strength, and modulus of elasticity. All readings were recorded digitally via a computer interface connected to the Instron system (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Fracture/deformation of retainer wire after load application.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc tests were used to compare groups. A significance level of p < 0.05 with an 80% confidence interval was applied.

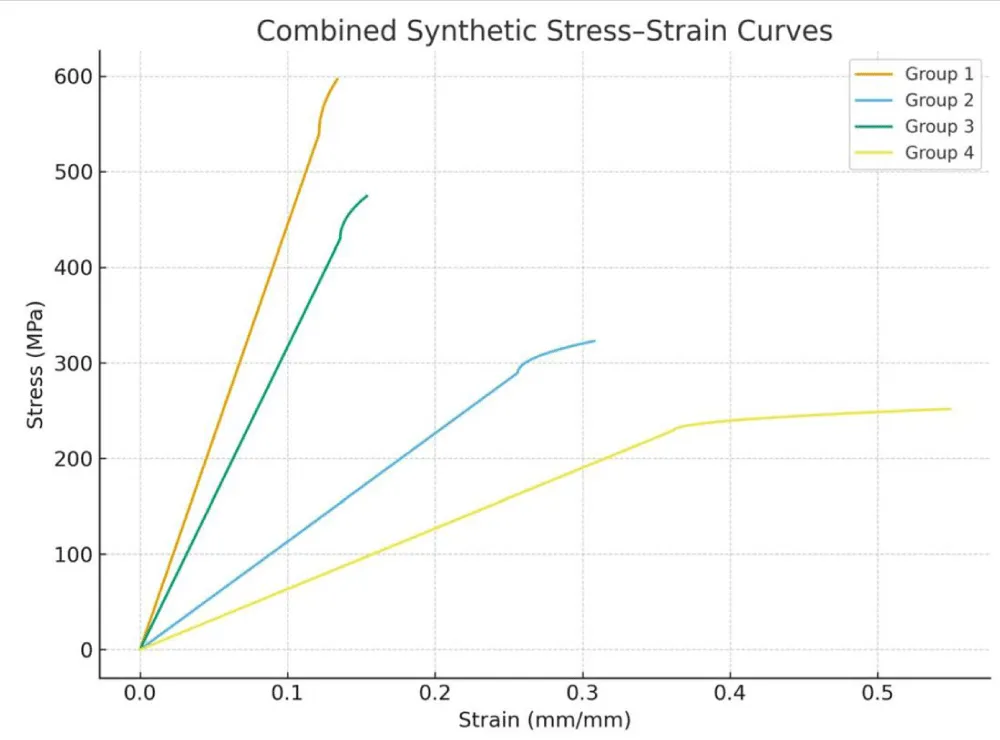

All specimens underwent tensile testing using a Universal Testing Machine, during which the applied load and corresponding deflection were continuously recorded. The load–deflection data were subsequently converted into stress–strain curves for every specimen. From these curves, the modulus of elasticity and yield strength were computed according to standard mechanical analysis protocols. This procedure was systematically performed for all nineteen specimens within each group, ensuring comprehensive mechanical characterization and permitting intergroup comparison of tensile performance and elastic behaviour (Table 2) (Figure 2).

| Table 2: Mean comparison of tensile strength, yield strength, young’s modulus between groups. | |||||||

| Tensile strength (MPa) | Yield strength (MPa) | Young’s modulus (GPa) | |||||

| Groups | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Mean | Std. Deviation | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Group 1 | 19 | 596.646 | 99.975 | 539.210 | 86.886 | 4.443 | 0.782 |

| Group 2 | 19 | 322.847 | 37.492 | 289.572 | 30.594 | 1.131 | 0.304 |

| Group 3 | 19 | 474.312 | 73.287 | 429.305 | 76.961 | 3.166 | 0.738 |

| Group 4 | 19 | 251.696 | 26.811 | 229.268 | 37.671 | 0.634 | 0.278 |

Figure 2: Stress-strain curves of four multistranded wires.

Intergroup comparison of mean Tensile strength was done using a way ANOVA test. The mean Tensile strength of 4 test wires were found to be significantly different. The difference between the mean Tensile strength of the 4 groups were further evaluated using Tukey’s HSD post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons. It was found that Group 1 showed the maximum mean Tensile strength (596.64 MPa) followed by the Group 3, Group 2 and Group 4 wires with 474.312 MPa, 322.847 MPa and 251.69 MPa respectively. The minimum and maximum Tensile strength for Group 1 was 548.459 MPa and 644.832 MPa, Group 3 was 438.989 MPa and 509.635 MPa, and Group 2 showed 304.777 MPa and 340.918 MPa, Group 4 was 238.77 MPa and 264.619 MPa respectively. Mean Tensile strength of Group 1 was more than Group 3 followed by Group 2 followed by Group 4. The comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Table 3) (Figure 3).

| Table 3: Intergroup comparison of tensile strength. | |||||

| Tensile Strength | |||||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | ||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Group 1 | 19 | 596.646 | 99.975 | 548.459 | 644.832 |

| Group 2 | 19 | 322.847 | 37.492 | 304.777 | 340.918 |

| Group 3 | 19 | 474.312 | 73.287 | 438.989 | 509.635 |

| Group 4 | 19 | 251.696 | 26.811 | 238.774 | 264.619 |

| p value | <0.001, S | ||||

Figure 3: Intergroup mean comparison of tensile strength.

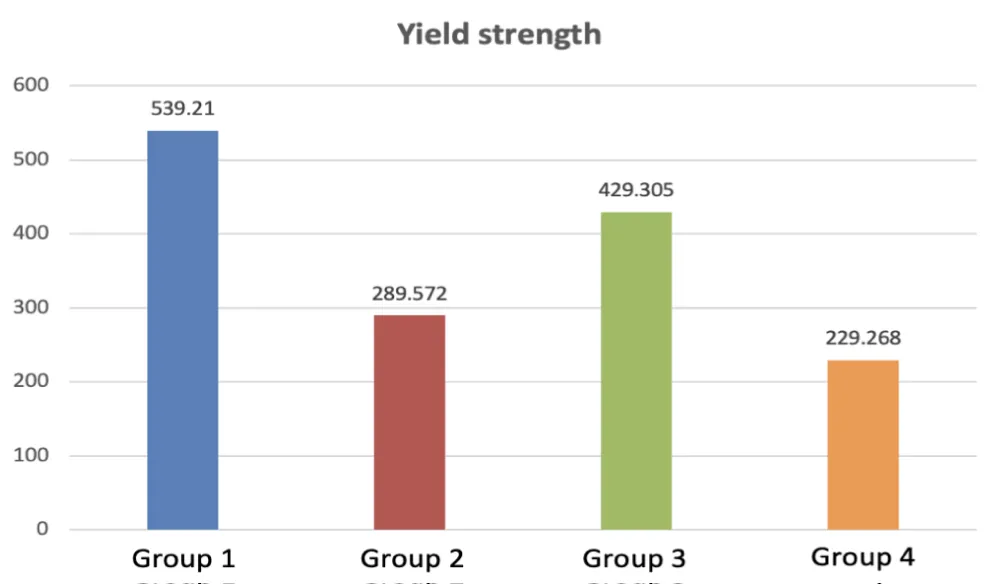

Intergroup comparison of mean Yield strength was done using one way ANOVA test. The mean Yield strength of 4 test wires were found to be significantly different. Post hoc pairwise comparison was done using post hoc Tukey’s test. It was seen that the Group 1 showed the maximum mean Yield strength (539.210 MPa) followed by the Group 3, Group 2 and Group 4 wires with 429.305 MPa, 289.572 MPa and 229.268 MPa respectively. The minimum and maximum Yield strength for Group 1 was 497.332 MPa and 581.08 MPa, Group 3 was 392.211 MPa and 466.399 MPa, and Group 2 showed 274.826 MPa and 304.318 MPa, Group 4 was 211.11 MPa and 247.425 MPa respectively. Mean Yield strength of Group 1 was more than Group 3 followed by Group 2 followed by Group 4. All of these comparisons showed statistical significance (p < 0.001) (Table 4) (Figure 4).

| Table 4: Intergroup comparison of yield strength. | |||||

| Yield Strength | |||||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | ||

| (Lower Bound) | (Upper Bound) | ||||

| Group 1 | 19 | 539.210 | 86.886 | 497.332 | 581.088 |

| Group 2 | 19 | 289.572 | 30.594 | 274.826 | 304.318 |

| Group 3 | 19 | 429.305 | 76.961 | 392.211 | 466.399 |

| Group 4 | 19 | 229.268 | 37.671 | 211.111 | 247.425 |

| p value | <0.001, S | ||||

Figure 4: Intergroup mean comparison of yield strength.

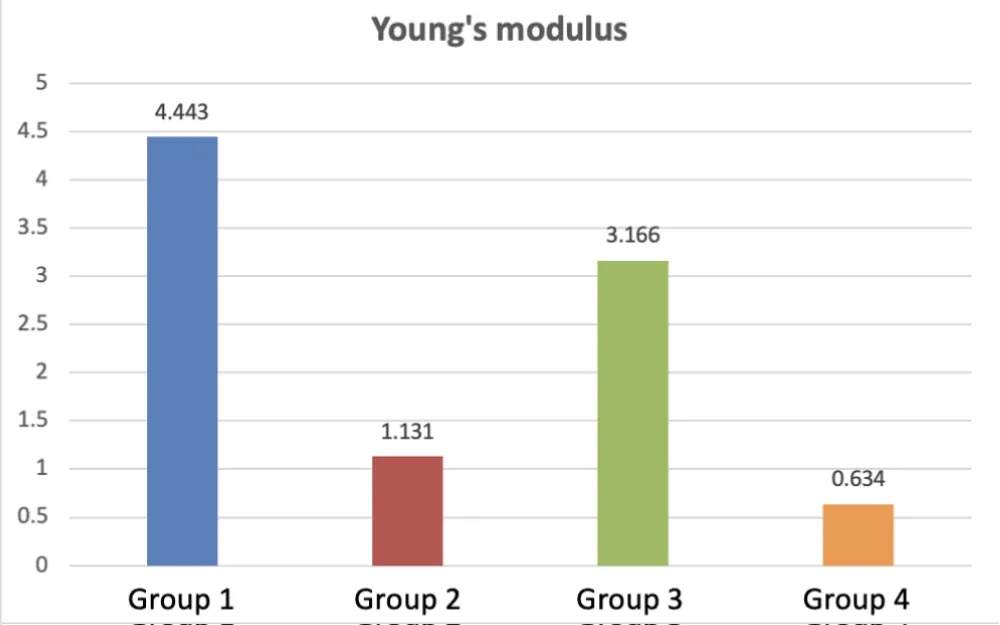

Intergroup comparison of mean Young’s modulus was done using one way ANOVA test. The mean Young’s modulus of 4 test wires were found to be significantly different. Post hoc pairwise comparison was done using post hoc Tukey’s test. It was seen that Group 1 showed the maximum mean Young’s Modulus (4.443 GPa) followed by the Group 3, Group 2 and Group 4 wire with 3.166 GPa, 1.131 GPa and 0.634 GPa respectively. The minimum and maximum Young’s Modulus for Group 1 was 4.066 GPa and 4.820 GPa, Group 3 was 2.810 GPa and 3.522 GPa, and Group 2 showed 0.985 GPa and 1.278 GPa, Group 4 was 0.500 GPa and 0.768 GPa respectively. Mean Young’s modulus of Group 1 was more than Group 3 followed by Group 2 followed by Group 4. All of these comparisons showed statistical significance (p < 0.001) (Table 5) (Figure 5).

| Table 5: Intergroup comparison of young’s modulus. | |||||

| Young’s Modulus | |||||

| Group | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | |

| (Lower Bound) | (Upper Bound) | ||||

| Group 1 | 19 | 4.443 | 0.782 | 4.066 | 4.820 |

| Group 2 | 19 | 1.131 | 0.304 | 0.985 | 1.278 |

| Group 3 | 19 | 3.166 | 0.738 | 2.810 | 3.522 |

| Group 4 | 19 | 0.634 | 0.278 | 0.500 | 0.768 |

| p value | <0.001, S | ||||

Figure 5: Intergroup mean comparison of young’s modulus.

Retention remains a pivotal phase of orthodontic treatment, particularly in preserving the alignment of the mandibular anterior segment, where relapse is most frequently observed. As established by Riedel, post-treatment relapse occurs because the periodontal fibers and surrounding soft tissues require extended time to reorganize after the active movement phase, creating a biologically vulnerable period during which teeth exhibit a natural tendency to return to their original positions. During this critical interval, retainers are indispensable for maintaining the orthodontically achieved tooth positions until complete periodontal remodeling is accomplished [11]. Fixed bonded retainers, especially multistranded stainless-steel wires, have therefore become widely favored due to their superior adaptability, reduced risk of distortion, enhanced durability, and proven ability to minimize long-term undesirable positional shifts [12]. Given that the biomechanical performance of retainer wires directly influences their clinical efficacy, longevity, and resistance to failure, the present study undertook a systematic evaluation of key mechanical properties—tensile strength, yield strength, and modulus of elasticity—among four commonly employed retainer wires differing in strand number and diameter using standardized tensile testing with an Instron Universal Testing Machine [13]. The findings of this investigation revealed a clear hierarchy of performance, with the seven-stranded 0.0175″ wire consistently exhibiting the highest tensile strength (596.646 MPa), yield strength (539.210 MPa), and modulus of elasticity (4.443 GPa), followed by the six-stranded 0.0175″ wire, the six-stranded 0.0195″ wire, and the five-stranded 0.0175″ wire, respectively. These results align closely with established literature, including studies by Zachrisson [14], Bearn [15], Urbye [16], Reicheneder [17], Yassameen A. Salih [18], Firdevs Günay [19], and others, all of whom demonstrated that increasing strand count enhances fracture resistance, optimizes stress distribution, and contributes to improved long-term stability of bonded retention systems. The superior performance of multistranded constructs is attributed to the greater flexibility and more homogeneous stress dissipation afforded by multiple intertwined filaments, which collectively reduce the propensity for localized fatigue failure and wire fracture.

A particularly noteworthy observation from the present study was the comparison between two six-stranded wires of differing diameters (0.0175″ and 0.0195″). Despite having the same strand configuration, the thinner 0.0175″ wire demonstrated superior tensile strength, higher yield strength, and a greater modulus of elasticity compared with the thicker 0.0195″ variant. This trend is consistent with findings from Firdevs Günay [20] and Annousaki [21], who reported that smaller-diameter multistranded wires may exhibit better mechanical behavior due to enhanced flexibility, improved stress accommodation, and reduced internal structural rigidity, whereas thicker wires—even with identical strand counts—may show diminished elastic performance and lower resistance to deformation. This highlights that wire diameter alone does not predict mechanical superiority; rather, performance emerges from the complex interplay between strand count, cross-sectional geometry, material flexibility, and the wire’s ability to distribute functional stresses efficiently.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that multistranded 0.0175″ wires—particularly seven-stranded designs—exhibit markedly superior biomechanical characteristics across all evaluated parameters compared with wires fabricated with fewer strands or greater diameters. Their enhanced tensile behavior, higher yield thresholds, and greater elastic stiffness collectively render them more effective in withstanding masticatory forces, minimizing deformation, and maintaining long-term stability of orthodontic outcomes. These findings provide compelling biomechanical evidence to guide clinicians in selecting retainer wires that optimize durability, reduce failure rates, enhance patient comfort, and minimize the risk of post-treatment relapse. By reinforcing the importance of strand architecture and mechanical properties in retainer performance, this study contributes meaningful insights to support evidence-based material selection for orthodontic retention protocols.

Within the constraints of this in vitro evaluation, the 7-stranded 0.0175” retainer wire (Group 1) exhibited the highest tensile strength, yield strength, and modulus of elasticity, outperforming all other wire configurations tested. These findings substantiate that increasing the strand complexity markedly enhances the wire’s fracture resistance, structural rigidity, and overall mechanical performance. Conversely, wires with fewer strands or comparable diameters demonstrated significantly reduced strength characteristics, indicating lower resistance to functional loading. Collectively, the results underscore the biomechanical superiority of higher-strand multistranded wires for fixed retention, suggesting their greater potential for long-term clinical stability, durability, and reliability. Future in-vivo investigations are warranted to corroborate these mechanical advantages under true oral environmental conditions.

Limitations

As an in vitro investigation, this study cannot replicate the dynamic oral environment, including saliva, temperature changes, masticatory forces, and microbial activity. The absence of periodontal tissues further limits assessment of true biomechanical response. Therefore, in-vivo research is needed to validate and strengthen these findings.

Source of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non profit sectors

- Kartal Y, Kaya B. Fixed orthodontic retainers: a review. Turkish journal of orthodontics. 2019;32(2):110. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5152/turkjorthod.2019.18080

- Singh A, Kapoor S, Mehrotra P, Bhagchandani J, Agarwal S. Comparison of Shear Bond Strength of Different Wire-Composite Combinations for Lingual Retention: An in Vitro Study. Journal of Indian Orthodontic Society. 2019;53(2):135-140. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0301574219840904

- Littlewood SJ, Millett DT, Doubleday B, Bearn DR, Worthington HV. Retention procedures for stabilising tooth position after treatment with orthodontic braces. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd002283.pub4

- Southard TE, Southard KA, Tolley EA. Periodontal force: a potential cause of relapse. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics. 1992;101(3):221-227. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-5406(92)70090-w

- Lyros I, Tsolakis IA, Maroulakos MP, Fora E, Lykogeorgos T, Dalampira M, et al. Orthodontic retainers—a critical review. Children. 2023;10(2):230. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020230

- Aye ST, Liu S, Byrne E, El-Angbawi A. The prevalence of the failure of fixed orthodontic bonded retainers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Orthodontics. 2023;45(6):645-661. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjad047

- Thompson SA. An overview of nickel–titanium alloys used in dentistry. International endodontic journal. 2000;33(4):297-310. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2591.2000.00339.x

- Meade MJ, Millett DT. Orthodontic bonded retainers: a narrative review. Dental Update. 2020;47(5):421-432. Available from: https://doi.org/10.12968/denu.2020.47.5.421

- Kapila S, Sachdeva R. Mechanical properties and clinical applications of orthodontic wires. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 1989;96(2):100-109. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3836125

- Samson RS, Varghese E, Uma E, Chandrappa PR. Evaluation of Bond Strength and Load Deflection Rate of Multi-stranded Fixed Retainer Wires: An: In-Vitro: Study. Contemporary clinical dentistry. 2018;9(1):10-14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/ccd.ccd_632_17

- Radlanski RJ, Zain ND. Stability of the bonded lingual wire retainer-a study of the initial bond strength. Journal of orofacial orthopedics Fortschritte der Kieferorthopadie Organ official journal Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Kieferorthopadie. 2004;65(4):321-335. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-004-0401-4

- Cacciafesta V, Sfondrini MF, Lena A, Scribante A, Vallittu PK, Lassila LV. Force levels of fiber-reinforced composites and orthodontic stainless steel wires: a 3-point bending test. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2008;133(3):410-413. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.047

- Cooke ME, Sherriff M. Debonding force and deformation of two multi-stranded lingual retainer wires bonded to incisor enamel: an in vitro study. The European Journal of Orthodontics. 2010;32(6):741-746. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjq017

- Baysal A, Uysal T, Gul N, Alan MB, Ramoglu SI. Comparison of three different orthodontic wires for bonded lingual retainer fabrication. Korean journal of orthodontics. 2012;42(1):39. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2012.42.1.39

- Zachrisson BU. Multistranded wire bonded retainers: from start to success. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2015;148(5):724-727. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.07.015

- Årtun J, Spadafora AT, Shapiro PA. A 3-year follow-up study of various types of orthodontic canine-to-canine retainers. European Journal of Orthodontics. 1997;19(5):501-509. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/19.5.501

- Reicheneder C, Hofrichter B, Faltermeier A, Proff P, Lippold C, Kirschneck C. Shear bond strength of different retainer wires and bonding adhesives in consideration of the pretreatment process. Head & Face Medicine. 2014;10:1-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-160x-10-51

- Salih YA, Al-Janabi MF. Tensile force measurement by using different lingual retainer wires, bonding materials types and thickness (A comparative in vitro study). Journal of Baghdad College of Dentistry. 2014;26(2):167-172. Available from: https://jbcd.uobaghdad.edu.iq/index.php/jbcd/article/view/470

- Gunay F, Oz AA. Clinical effectiveness of 2 orthodontic retainer wires on mandibular arch retention. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2018;153(2):232-238. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.06.019

- Alhakim AI, Alhuwaizi AF. Assessment of the Impact of Adhesive and Wires Types on the Tensile Bond Strength of Fixed Lingual Retainers Used in Orthodontics: An In Vitro Study. Dental Hypotheses. 2023;14(4):103-106. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/dhyp/fulltext/2023/14040/assessment_of_the_impact_of_adhesive_and_wires.4.aspx

- Radlanski RJ, Zain ND. Stability of the bonded lingual wire retainer-a study of the initial bond strength. J Orofac Orthop. 2004;65(4):321-335. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-004-0401-4