More Information

Submitted: December 05, 2025 | Accepted: December 17, 2025 | Published: December 18, 2025

Citation: Dolo SS, Diallo B. Prevalence and Determinants of Oral Health Conditions among Adolescent Female Detainees in Bamako, Mali: A Cross-sectional Study. J Clin Adv Dent. 2025; 9(1): 021-031. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jcad.1001052

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcad.1001052

Copyright license: © 2025 Dolo SS, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Oral health; Dental caries; Periodontal disease; Adolescents; Prison health; Mali

Prevalence and Determinants of Oral Health Conditions among Adolescent Female Detainees in Bamako, Mali: A Cross-sectional Study

Sulemana Seidu Dolo* and Baba Diallo

Ministry of Health and Social Development, Department of Odontostomatology, Bamako, Mali

*Corresponding author: Sulemana Seidu Dolo, Ministry of Health and Social Development, Department of Odontostomatology, Bamako, Mali, Email: Dolo, [email protected]

Background: Oral health is a critical yet often neglected aspect of public health in low-income countries, particularly among vulnerable populations such as incarcerated adolescents. This study aimed to assess the prevalence, types, and determinants of oral health conditions among adolescent female detainees at the Bolé Detention and Rehabilitation Center in Bamako, Mali.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from January to February 2025 among 90 adolescent female detainees aged 12–17 years. Data were collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted from the WHO Oral Health Surveys (5th Edition) and clinical oral examinations following WHO criteria. Dental caries was assessed using the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted, with variables significant at p < 0.20 included in multivariable logistic regression models to identify independent predictors of dental caries.

Results: The mean age of participants was 15.2 years (SD ± 1.4), with the majority aged 14–15 years (63.3%). Most participants had primary-level education (33.3%) and were unemployed before detention (55.4%). Oral hygiene practices showed that 74.4% brushed their teeth at least once daily, with 79.1% using a toothbrush and 20.9% using a chewing stick. Clinical examination revealed a high prevalence of oral conditions: dental caries (66.7%), periodontal disease (22.2%), oral ulcers (6.7%), and dental malocclusion (4.4%). Improper brushing technique was observed in 92.2% of participants. Among participants with dental caries, 40% required urgent treatment (extractions or restorations), while 26.7% needed routine preventive care. Most participants (61.1%) identified poor oral hygiene as the main cause of dental disease.

Conclusion: Oral diseases are highly prevalent among adolescent female detainees in Bamako, reflecting gaps in preventive care and oral hygiene practices. Integration of structured oral health education, routine dental screenings, and provision of hygiene materials into detention healthcare programs is urgently needed to improve clinical outcomes and overall well-being in this vulnerable population.

Oral diseases are among the most prevalent noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) globally, affecting individuals across all age groups and socioeconomic strata. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that nearly 3.5 billion people worldwide suffer from oral conditions, primarily dental caries, periodontal diseases, tooth loss, and oral cancers. Beyond pain and functional impairment, oral diseases significantly affect quality of life, nutrition, educational performance, and overall well-being [1]. Importantly, oral diseases share several modifiable risk factors with other NCDs, including tobacco use, unhealthy diets high in free sugars, and harmful alcohol consumption.

Globally, the burden of oral diseases is unevenly distributed, with the highest prevalence observed in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where preventive services are limited and access to dental care remains inadequate. Although the cost of treating oral diseases ranks among the top three health expenditures in most industrialized countries, preventive oral health receives minimal investment in resource-constrained settings [2].

These structural inequities contribute to persistently high levels of untreated oral disease in vulnerable populations.

In Africa, oral health disparities mirror these global inequities. Epidemiological evidence indicates that 60–90% of school-aged children and nearly all adults experience dental caries, with particularly high levels of untreated disease [3]. Untreated oral conditions in sub-Saharan Africa are associated with significant morbidity, including pain, infection, impaired nutrition, and school absenteeism [4]. Despite these consequences, oral health remains one of the most neglected components of public health programming across the region, often excluded from national NCD strategies and primary healthcare priorities [5].

Incarcerated populations represent a particularly vulnerable group with disproportionately poor health outcomes, including a high burden of oral diseases. Studies conducted in prison settings globally and in parts of Africa report elevated prevalence of dental caries, periodontal disease, tooth loss, and poor oral hygiene practices, driven by overcrowding, psychological stress, limited access to hygiene materials, and restricted availability of professional dental services [6]. The prison environment, combined with socioeconomic disadvantage and pre-existing poor health behaviors, further exacerbates oral health inequalities among detainees [7].

However, despite increasing recognition of oral health as a public health priority, evidence on oral health among detained adolescents in West Africa remains extremely limited [8]. In Mali, available oral health data are sparse and largely derived from hospital-based studies, which indicate that dental caries and periodontal diseases dominate the oral morbidity profile [9]. National, community-based, or institution-based epidemiological data are notably lacking, particularly among adolescents and institutionalized populations such as those in detention or rehabilitation facilities. Existing studies in sub-Saharan Africa predominantly focus on general school-based populations or adult prisoners and are largely concentrated in Southern and Eastern Africa, leaving a substantial evidence gap in West African contexts [10].

Moreover, where prison-based oral health research exists, data are rarely disaggregated by age or sex, thereby obscuring the specific oral health needs of adolescent girls in detention.

This lack of age- and gender-specific evidence hampers the development of targeted prevention strategies, appropriate resource allocation, and the integration of oral health services into juvenile justice and rehabilitation healthcare systems. The Bolé Detention and Rehabilitation Center, established in Bamako in 1998, houses adolescent girls and women in conflict with the law. Conditions within the facility, including overcrowding, inadequate hygiene infrastructure, and limited access to preventive dental services, may place detained adolescents at heightened risk of oral disease.

Understanding the oral health status of detained adolescents is therefore essential for designing context-specific preventive and therapeutic interventions. Evidence from other African settings suggests that prison-based oral health programs can substantially reduce disease burden when integrated into existing correctional healthcare services [11]. Against this backdrop of limited data in West Africa, this study aimed to describe the epidemiological profile of oral diseases among adolescent female detainees in Bamako, Mali, and to identify behavioral and environmental factors associated with poor oral health. The findings are intended to provide baseline evidence to inform public health planning, support equitable oral healthcare provision, and strengthen health services within juvenile detention settings.

Theoretical and conceptual framework

Understanding oral health outcomes among adolescent detainees requires a holistic framework that captures the interplay between individual behaviors, biological susceptibility, and the broader social and institutional environment. This study, therefore, integrates three complementary frameworks: the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Social Ecological Model (SEM), and established biological mechanisms underlying dental caries and periodontal disease. Together, these frameworks provide a comprehensive grounding for interpreting behavioral patterns, identifying systemic determinants, and explaining observed clinical outcomes.

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA): The TRA posits that human behavior is primarily driven by behavioral intentions, which are shaped by an individual’s attitudes toward the behavior and subjective norms—that is, perceived social pressures from peers, parents, or authority figures [12]. Within detention environments, this model is especially relevant because adolescents often have limited autonomy and rely heavily on peer influence and institutional routines [13].

For example, even when detainees know the importance of brushing their teeth, their intention to perform effective oral hygiene may be constrained by:

Inadequate access to toothbrushes or toothpaste;

Peer dynamics that discourage consistent hygiene;

Institutional schedules that limit hygiene routines, and Low self-efficacy in performing correct brushing techniques.

Empirical studies show that knowledge alone is insufficient to ensure healthy oral behaviors among adolescents, particularly when structural barriers persist. The TRA, therefore, guides this study’s examination of how attitudes and social norms influence oral hygiene practices in a restricted and resource-limited setting.

Social Ecological Model (SEM): While TRA focuses on individual cognition and social influence, the Social Ecological Model extends the analysis to broader contextual factors. The SEM conceptualizes health behaviors as the result of interactions across multiple levels:

Individual (knowledge, skills, biological susceptibility),

Interpersonal (peer networks, shared routines in detention),

Institutional (access to hygiene supplies, presence of dental services),

Social Ecological Model (SEM): (cultural norms about oral care), and

Policy (national prison health regulations).

Applying the SEM highlights the systemic barriers shaping oral health outcomes among detainees. Previous studies in African correctional facilities report shortages of basic hygiene materials, irregular access to dentists, and absence of preventive programs, all of which contribute to poor oral health [14]. Within this context, adolescent detainees face environmental constraints that significantly undermine their capacity to adopt and maintain healthy oral hygiene behaviors, even when motivated to do so.

Biological rationale for oral disease

Dental caries and periodontal disease develop through well-established biological pathways involving:

Cariogenic bacteria (e.g., Streptococcus mutans);

Frequent intake of fermentable carbohydrates;

Accumulation of dental plaque;

Inadequate salivary flow;

Host immune responses;

Adolescents in detention may experience heightened biological vulnerability due to:

Dietary monotony and high sugar content;

Psychological stress, which reduces salivary flow.

Poor nutritional status, associated with weakened immunity;

Close living quarters, which increase the transmission of pathogens.

These physiological mechanisms help explain the high prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease observed in this study. The biological rationale strengthens the study’s argument that both behaviors and systemic conditions contribute to poor oral outcomes.

Integrated framework for the study

Integrating the TRA, SEM, and biological mechanisms creates a robust conceptual foundation that captures the multifactorial nature of oral health among detained adolescents.

TRA helps explain why adolescents intend—or fail—to practice proper oral hygiene by examining attitudes, perceived norms, and behavioral intentions.

The SEM contextualizes how the detention environment limits or facilitates these intentions, emphasizing the role of structural determinants such as access to supplies, institutional policies, and peer interactions.

Biological mechanisms provide the physiological explanations linking behaviors and environments to clinical outcomes, making it possible to understand why certain patterns (e.g., high caries rates) emerge in this population.

Together, these frameworks justify the selection of variables (oral hygiene behaviors, availability of hygiene materials, clinical indicators) and guide the interpretation of findings. The integrated approach aligns with modern public health science, which emphasizes the importance of considering behavioral, biological, and social determinants simultaneously to understand health disparities in marginalized populations [15].

This integrated framework is particularly appropriate for detention settings, where individual behavior is deeply intertwined with institutional constraints and biological susceptibility [16].

It also strengthens the study’s ability to draw meaningful conclusions about intervention strategies, suggesting that effective solutions must address not only personal knowledge and attitudes but also systemic barriers and biological vulnerabilities.

Objectives

The overall objective of this study was to assess the oral health status and related behavioral factors among adolescent female detainees at the Bolé Detention and Rehabilitation Center in Bamako, Mali.

Specifically, the study aimed to:

Determine the prevalence and types of oral diseases (including dental caries, periodontal diseases, oral ulcers, and malocclusion) among adolescent female detainees.

Describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population and their association with oral health status.

Assess oral hygiene behaviors and practices, such as frequency of toothbrushing, use of toothbrushes or chewing sticks, and brushing techniques.

Identify detainees’ knowledge and perceptions regarding the causes and prevention of oral diseases.

Provide evidence-based recommendations for strengthening oral health promotion and preventive interventions within correctional facilities in Mali.

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the prevalence and determinants of oral health conditions among adolescent female detainees at the Bolé Detention and Rehabilitation Center in Bamako, Mali. This design was appropriate for estimating the burden of oral diseases and identifying associated factors at a specific point in time within a closed institutional population.

Study setting

The study took place at the Bolé Detention and Rehabilitation Center for Women and Girls in Bamako, which houses adolescent girls and women in conflict with the law. Healthcare services at the facility are limited to a basic infirmary, with irregular visits from external medical and dental professionals, primarily for emergency care. The limited access to preventive and routine dental services underscores the relevance of assessing oral health needs in this population.

Study population

The study population comprised all adolescent female detainees aged 12–17 years present in the facility during the data collection period (January–February 2025). At the time of the study, 115 adolescents were residing in the facility.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: Female adolescents aged 12–17 years.

Present in the facility during the data collection period.

Physically able to undergo oral examination.

Provided assent, with consent obtained from legal authorities.

Exclusion criteria: Adolescents with medical conditions preventing oral examination.

Adolescents temporarily visiting or in transfer.

Adolescents who refused participation.

Sample size and sampling technique

A census (total population) sampling approach was used to include all eligible detainees. Of the 115 adolescents, 90 met eligibility criteria and consented to participate, resulting in a final sample of 90 participants (78.3% of the total adolescent population).

This approach minimized sampling bias and ensured comprehensive coverage of the eligible population.

Data collection tools and procedures

Data were collected using a combination of structured interviews and clinical oral examinations.

Questionnaire:

A structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire, adapted from the WHO Oral Health Surveys (5th Edition), was used to collect information on:

Sociodemographic characteristics (age, education, pre-detention occupation);

Oral hygiene practices (frequency, duration, type of toothbrush or chewing stick);

Dietary habits, particularly sugar consumption;

Dental service utilization;

Self-reported oral health status.

Clinical examination

A trained dentist conducted intraoral examinations under natural light using sterile mouth mirrors and WHO CPI probes. Dental caries was assessed according to WHO criteria using the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index. Periodontal disease, oral ulcers, and malocclusion were also recorded. Strict infection prevention protocols were followed throughout the examinations.

Examiner calibration and quality control

To ensure accuracy and reliability of clinical assessments, the following procedures were implemented:

Training and calibration: The principal examiner underwent two days of intensive training on WHO oral health criteria, DMFT scoring, and periodontal assessment. Calibration exercises were conducted on 10 adolescent volunteers outside the study population.

Intra-examiner reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa, yielding 0.87 for dental caries and 0.84 for periodontal assessment, indicating excellent agreement.

Supervised re-examinations: A senior dental supervisor randomly re-examined 10% of participants to verify DMFT and periodontal scoring. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus before data entry.

Data entry verification: Clinical data were recorded on pre-coded forms and double-entered into Epi Info v7.2. Any inconsistencies between duplicate entries were cross-checked against source forms and corrected before analysis.

Assessment of toothbrushing technique

The toothbrushing technique was assessed through direct observation. Participants were asked to demonstrate their usual toothbrushing method using a toothbrush under the supervision of the examining dentist.

The assessment followed criteria adapted from WHO oral health education guidelines and standard dental hygiene practices, focusing on brushing movements, coverage of tooth surfaces (buccal, lingual, and occlusal), attention to the gingival margin, and brushing duration. Techniques were classified as either proper or improper based on these observed criteria [17].

Variables

Dependent variable: Presence of dental caries (DMFT score)

Independent variables:

Sociodemographic factors (age, education, employment status);

Oral hygiene behaviors (frequency, duration, type of toothbrush);

Sugar consumption;

Duration of detention;

Access to hygiene materials and dental care;

Self-reported oral health status;

Operational definitions

Dental caries: Presence of one or more decayed, missing due to caries, or filled teeth.

DMFT Index: Sum of decayed (D), missing (M), and filled (F) teeth.

Low: 0–4

Moderate: 5–9

High: ≥10

Regular tooth brushing: Brushing teeth ≥2 times per day

High sugar intake: Consumption of sugary snacks or drinks ≥1 time/day

Access to dental care: Ability to obtain dental treatment after reporting symptoms

Improper brushing technique

Brushing behavior characterized by failure to perform effective plaque-removal movements, including one or more of the following: horizontal scrubbing without systematic coverage of all tooth surfaces; omission of gingival margins; brushing limited to anterior teeth only; inadequate angulation of the toothbrush (i.e., not placing bristles at approximately 45° to the gingival margin); or brushing duration less than two minutes. Participants exhibiting any of these deficiencies during direct observation were classified as having an improper brushing technique.

Data analysis

Data were entered into Epi Info version 7.2 and analyzed using SPSS version 26.

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) summarized participants’ characteristics and DMFT scores.

Bivariate analyses included Chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent t-tests for continuous variables to examine associations between potential determinants and dental caries.

Variables with p - values < 0.20 in bivariate analyses were included in a multivariable logistic regression model to identify independent predictors of dental caries.

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Variables with p - values < 0.20 in bivariate analyses were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. This relatively liberal threshold was intentionally selected to avoid premature exclusion of potentially important confounders or predictors that may not show strong associations in unadjusted analyses but could become significant after controlling for other variables. This approach is widely recommended in epidemiological modeling to ensure a comprehensive assessment of factors associated with health outcomes and to reduce the risk of residual confounding.

Quality assurance

Data collectors were trained in study protocols, and pre-testing of the questionnaire was conducted to ensure clarity and reliability. Clinical examinations followed WHO-standardized procedures [18], and double-entry verification was used to minimize data entry errors.

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 90 adolescent female detainees participated in the study. The mean age was 15.2 years (SD ± 1.4), with the majority aged 14–15 years (63.3%) and 16–17 years (33.3%). Regarding education, 36.7% had no formal education, 33.3% had attained primary-level education, and 30.0% had secondary-level education. Pre-detention occupations included unemployment (55.4%), street vending (25.5%), and being students (16.6%) (Table 1).

| Table 1: Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants (n = 90). | |

| Characteristic | N (%) |

| Age (years) | |

| 12–13 | 3 (3.3) |

| 14–15 | 57 (63.3) |

| 16–17 | 30 (33.3) |

| Education Level | |

| None | 33 (36.7) |

| Primary | 30 (33.3) |

| Secondary | 27 (30.0) |

| Pre-detention Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 50 (55.4) |

| Street vending | 23 (25.5) |

| Student | 15 (16.6) |

| Other | 2 (2.2) |

Oral hygiene practices

Most participants reported brushing their teeth at least once daily (74.4%), with 79.1% using a toothbrush and 20.9% using a chewing stick. The most common reported brushing duration was 4 minutes (43.3%). Despite these reported practices, improper brushing technique was observed in 92.2% of participants (Tables 2,3).

| Table 2: Oral Hygiene Practices. | |

| Practice | N (%) |

| Toothbrushing frequency | |

| ≥1 time/day | 67 (74.4) |

| <1 time/day | 23 (25.6) |

| Type of cleaning material | |

| Toothbrush | 71 (79.1) |

| Chewing stick | 19 (20.9) |

| Brushing duration (minutes) | |

| <2 | 28 (31.1) |

| 2–4 | 23 (25.5) |

| 4+ | 39 (43.3) |

| Proper brushing technique | |

| Yes | 7 (7.8) |

| No | 83 (92.2) |

| Table 3: Oral Health Conditions. | ||

| Condition | N (%) | Notes / Treatment Needs |

| Dental caries | 60 (66.7) | Urgent: 36 (40%); Preventive: 24 (26.7%) |

| Periodontal disease | 20 (22.2) | Scaling and oral hygiene education |

| Oral ulcers | 6 (6.7) | Symptomatic treatment needed |

| Dental malocclusion | 4 (4.4) | Referral for orthodontic evaluation |

Despite self-reported regular toothbrushing, direct observation revealed that 92.2% of participants demonstrated improper brushing techniques, primarily characterized by horizontal scrubbing, incomplete coverage of tooth surfaces, and neglect of gingival margins.

Oral health conditions

Clinical examination revealed a high burden of oral diseases: Clinical examination revealed a high burden of oral diseases among participants. Dental caries affected 66.7% of adolescents. The mean DMFT score was 4.6 ± 2.3, with values ranging from 0 to 11, indicating a substantial burden of untreated dental disease. Periodontal disease was present in 22.2% of participants, oral ulcers in 6.7%, and dental malocclusion in 4.4%. Among participants with dental caries, 40% required urgent treatment (extractions or restorations), while 26.7% required routine preventive care, including fluoride application and oral hygiene instruction. Participants with periodontal disease mainly required scaling and professional cleaning, accompanied by oral hygiene education (Table 4).

| Oral Health Indicator | n (%) | Mean ± SD (range) |

| DMFT | 90 (100%) | 4.6 ± 2.3 (0–11) |

| Table 4: Dental Caries Burden. | |

| Value | |

| DMFT mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 2.3 |

| DMFT range | 0–11 |

| Decayed (D) teeth mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 1.8 |

| Missing (M) teeth mean ± SD | 0.9 ± 1.2 |

| Filled (F) teeth mean ± SD | 0.6 ± 0.9 |

Location of oral lesions

Oral lesions were more frequently located in the mandible (58.4%) than in the maxilla (41.6%) (Table 5).

| Table 5: Distribution of Oral Lesions by Location. | |

| Location of Lesion | N (%) |

| Mandible | 70 (58.4) |

| Maxilla | 50 (41.6) |

| Total | 120 (100) |

| Note : Percentages represent all lesions ; multiple lesions per participant possible. | |

Knowledge of causes of oral health conditions

A majority of participants (61.1%) identified poor oral hygiene as the primary cause of oral health problems, while smaller proportions attributed oral diseases to high sugar intake or other factors, indicating a baseline awareness of risk factors despite gaps in effective practice (Table 6).

| Table 6: Knowledge of Causes of Oral Health Conditions. | |

| Cause of Oral Disease | N (%) |

| Poor oral hygiene | 55 (61.1) |

| High sugar intake | 18 (20.0) |

| Other / unspecified factors | 17 (18.9) |

| Total | 90 (100) |

Summary of oral health needs

Overall, the findings highlight substantial unmet oral health needs within the detention facility, including:

High prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease;

Limited availability of oral hygiene resources;

Insufficient access to preventive and curative dental services;

Knowledge-practice gaps in oral hygiene behaviors;

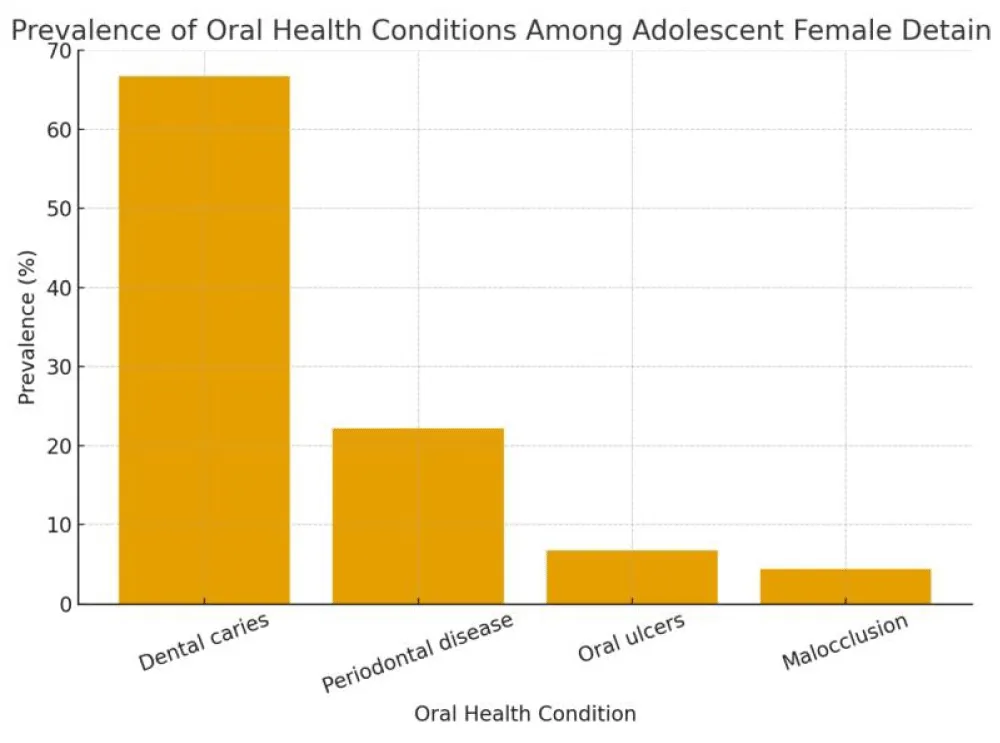

These results underscore the urgent need for structured oral health interventions, including education, regular screening, and integration of dental services into the facility’s healthcare system (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of Oral Health Conditions.

In multivariable logistic regression, participants who brushed their teeth ≥2 times per day had significantly lower odds of dental caries (OR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.14–0.72; p = 0.006), whereas high sugar intake was associated with higher odds of caries (OR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.05–4.21; p = 0.036). Age, education, and duration of detention showed non-significant associations but demonstrated meaningful effect sizes, suggesting potential contributions to risk that may warrant further study (Figure 2).

| Figure 2: Multivariable Logistic Regression (Oral Health). | |||

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age (years) | 1.25 | 0.95–1.65 | 0.11 |

| Education (secondary vs none) | 0.48 | 0.22–1.03 | 0.06 |

| Toothbrushing ≥2/day | 0.32 | 0.14–0.72 | 0.006 |

| High sugar intake | 2.10 | 1.05–4.21 | 0.036 |

| Duration of detention (>6 mo) | 1.85 | 0.95–3.61 | 0.07 |

Interpretation of multivariable predictors of dental caries

Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to identify independent predictors of dental caries among adolescent female detainees. The analysis included variables with p < 0.20 in bivariate analyses, and results are summarized in Figure 1 (see revised table with ORs and 95% CIs).

Toothbrushing frequency (≥2 times/day)

OR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.14–0.72; p = 0.006

Adolescents who brushed their teeth at least twice daily had 68% lower odds of developing dental caries compared to those brushing less frequently. This strong protective effect highlights the critical role of frequent oral hygiene, even in a resource-limited detention setting.

High sugar intake (≥1 sugary snack/drink per day)

OR = 2.10; 95% CI : 1.05–4.21 ; p = 0.036

Adolescents consuming sugary foods or drinks daily had more than twice the odds of dental caries relative to those with lower sugar intake. This emphasizes dietary habits as a key modifiable risk factor in detention centers, where meals may be carbohydrate-heavy or include sugary snacks.

Education level (secondary vs. none)

OR = 0.48; 95% CI : 0.22–1.03 ; p = 0.06

Adolescents with secondary-level education tended to have lower odds of dental caries, though this association did not reach statistical significance. The effect size suggests that higher education may confer some protection through better oral health knowledge and self-care practices, consistent with studies in other LMIC contexts.

Duration of detention (>6 months)

OR = 1.85; 95% CI : 0.95–3.61 ; p = 0.07

Adolescents detained for more than six months showed a tendency toward higher caries risk, likely due to prolonged exposure to institutional constraints, limited dental care access, and environmental stressors. While not statistically significant, the magnitude of the odds ratio indicates a potentially important factor for program planning.

Age (years)

OR = 1.25; 95% CI: 0.95–1.65; p = 0.11

Older adolescents showed a non-significant increase in caries odds, reflecting cumulative exposure over time to risk factors such as sugar consumption and inadequate hygiene.

Overall interpretation

Behavioral factors such as frequent toothbrushing and sugar consumption were the strongest and statistically significant predictors of dental caries, demonstrating the direct impact of daily habits even within a constrained detention environment.

Sociodemographic and institutional factors (education, duration of detention, age) showed moderate effect sizes, indicating that interventions addressing both individual behaviors and structural barriers are needed to reduce caries prevalence effectively.

Reporting ORs with 95% CIs allows readers to appreciate both the strength and precision of these associations, moving beyond p - values to assess practical relevance for programmatic interventions.

This study highlights a significant burden of oral health conditions among adolescent female detainees at the Bolé Detention and Rehabilitation Center in Bamako, Mali. Dental caries was the most prevalent condition, affecting 66.7% of participants, with a mean DMFT score of 4.6 ± 2.3 (range: 0–11). Periodontal disease was also common, affecting 22.2% of participants, while oral ulcers and malocclusion were less frequent.

The mean DMFT observed in this population is moderately high when compared to general adolescent populations in West Africa. For instance, studies from Nigeria and Ghana reported mean DMFT scores of 2.8–3.5 among school-aged adolescents [19], while studies in South Africa and Cameroon reported scores ranging from 3.2 to 4.0 [20]. The slightly higher DMFT in our study may reflect the combined effects of incarceration-related constraints, including limited access to oral hygiene materials, inadequate preventive care, and high sugar consumption within the facility.

Globally, LMICs often report higher DMFT scores among institutionalized or socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents compared to non-incarcerated peers.

For example, studies from Brazil, India, and Ethiopia documented mean DMFT scores of 4–6 among youth in juvenile detention centers, reflecting similar structural and behavioral risk factors, such as irregular dental visits, poor oral hygiene practices, and dietary monotony [21]. These findings align with our results, suggesting that the detention environment itself is a critical determinant of oral health, independent of general population trends.

Despite most participants reporting regular tooth brushing (≥1 time/day), improper brushing techniques were observed in 92.2% of participants, highlighting a strong knowledge–practice gap. This mirrors findings from other LMIC detention studies, where awareness of oral hygiene did not translate into effective plaque removal, often due to inadequate supervision, limited access to toothpaste, and overcrowding [22].

Mandibular lesions predominated (58.4%), consistent with studies in juvenile detention centers in Nigeria and Kenya [23]. This pattern may reflect mechanical difficulty in cleaning posterior teeth, delayed care seeking, and limited professional dental interventions.

In addition, biological factors such as malnutrition, psychological stress, and reduced salivary flow in detained adolescents may exacerbate caries development and periodontal disease, reinforcing the multifactorial etiology of oral health problems in these settings.

Comparing our findings to those of other LMICs, the prevalence and DMFT magnitude underscore the combined impact of individual, behavioral, and systemic determinants [24]. While community-based adolescents in Mali and neighboring countries show slightly lower DMFT scores, detention amplifies risk due to structural barriers, restricted autonomy, and inadequate oral healthcare infrastructure [25]. These differences highlight the urgent need for targeted interventions within correctional facilities, rather than solely relying on community-based oral health programs.

Overall, our results add to the limited literature on oral health among incarcerated adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa [26], emphasizing critical gaps in preventive and curative care, and providing a quantitative baseline (mean DMFT 4.6 ± 2.3) to guide future interventions and policy planning.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and convenient sampling in a single facility may affect generalizability. The study did not evaluate key determinants such as detailed dietary intake, mental health, substance use, or prior access to dental care. Self-reported oral hygiene behaviors may be affected by recall and social desirability bias, and the absence of radiographs could underestimate disease prevalence.

This study demonstrates a substantial burden of oral health problems among adolescent female detainees in Bamako, with dental caries and periodontal disease emerging as the most prevalent conditions. Dental caries affected 66.7% of participants, with a mean DMFT score of 4.6 ± 2.3 (range: 0–11), indicating a moderate to high disease burden for some individuals. These findings align with studies from other low- and middle-income countries, where incarcerated adolescents consistently experience poorer oral health outcomes than their non-detained peers. Similar high prevalence levels have been reported among juvenile detainees in Nigeria and South Africa, where caries rates exceeded 60% and periodontal problems were common due to inadequate hygiene practices and limited access to care [27].

Despite most participants reporting regular tooth brushing, the overwhelmingly high rate of improper brushing techniques (92.2%) reveals a strong knowledge–practice gap, consistent with findings from juvenile correctional centers in Kenya, Brazil, and India [28].

Limited availability of dental care within the detention facility further exacerbates oral health challenges. Comparable systemic gaps have been documented globally, including in Ethiopia, Uganda, and Pakistan, where shortages of hygiene supplies, absence of preventive programs, and poor access to treatment contribute to high rates of untreated dental disease [29].

Addressing these gaps requires comprehensive, multifaceted interventions that go beyond clinical care. Evidence from prison-based oral health programs in the United States, Canada, and Europe demonstrates that combining oral health education, routine screenings, supervised tooth brushing, and provision of fluoride products can significantly reduce caries incidence and improve periodontal outcomes among detained youth [30].

Integrating oral health into juvenile justice policies and public health programs, particularly those targeting vulnerable adolescents, can foster a rights-based approach supporting rehabilitation and reintegration.

In conclusion, improving oral health outcomes for detained adolescent girls in Bamako requires strengthening preventive education, supplying adequate hygiene materials, ensuring routine dental screenings, including DMFT assessment, and incorporating dental services into the broader correctional healthcare framework. Addressing the mean DMFT burden is critical not only for oral health but also for enhancing overall well-being, restoring dignity, and supporting long-term social reintegration of incarcerated adolescents.

Policy recommendations

Based on the study findings, including the mean DMFT score, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

Provision of adequate hygiene materials

Ensure all detainees have regular access to toothbrushes, fluoride toothpaste, and other oral hygiene essentials to prevent further increases in DMFT scores.

Structured oral health education programs

Implement supervised brushing sessions and educational workshops to teach proper brushing techniques and reinforce the link between oral hygiene and caries prevention.

Routine dental screening and preventive care

Establish regular oral health check-ups, including DMFT assessment, scaling, fluoride applications, and treatment of carious lesions, to reduce both prevalence and severity of dental disease.

Integration into prison health policy

Incorporate oral health as a standard component of detention healthcare programs, aligning with national and WHO guidelines for adolescent health.

Training of health personnel

Train detention healthcare staff on oral health promotion, early identification of dental diseases, and referral pathways for advanced care, ensuring systematic monitoring of DMFT trends.

Multisectoral collaboration

Encourage partnerships with local dental schools, NGOs, and public health institutions to provide preventive, curative, and educational support within detention facilities.

Monitoring and evaluation

Establish a system for routine data collection on oral health status, including mean DMFT and distribution ranges, to guide evidence-based program adjustments and track improvements over time.

Implementing these recommendations can substantially reduce caries incidence, improve oral hygiene behaviors, and enhance overall health and quality of life among adolescent detainees, creating a sustainable foundation for long-term oral health improvements in correctional settings.

Declaration

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of Mali. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians. Participation was voluntary, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

Declaration of adherence to the Belmont report ethical principles

As the author of this manuscript, I hereby affirm that this work adheres to the three core ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice. All research involving human subjects was conducted with proper informed consent, recognizing the autonomy of individuals and providing additional protection for those with diminished autonomy.

This work upholds the principle of Beneficence by maximizing possible benefits while minimizing potential harm to research participants. The assessment of risks and benefits was carefully conducted to ensure the welfare of all subjects. Furthermore, the principle of Justice has been honored through the fair selection of research subjects and equitable distribution of research burdens and benefits across different populations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This manuscript does not contain any identifiable data from individual persons.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions involving a vulnerable population in a detention setting. Still, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: SSD and BD; Data curation: SSD; Formal Analysis: SSD and BD; Investigation: SSD and BD; Methodology: SSD and BD; Project administration: SSD and BD; Resources: SSD and BD; Validation: SSD; Visualization: SSD; Writing – original draft: SSD and BD; Supervision: BD; Writing – review and editing: SSD and BD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the article.

The author(s) wish to thank the administration of the Bolé Detention Center, the participating adolescent girls, and the health staff who assisted with data collection.

Appreciation is also extended to INFSS: Institut National de Formation en Sciences de la Santé and (CHU-C NOS) Centre Hospitalière Universitaire, Centre National de Odontostomatologie Bamako, Mali.

- World Health Organization. The global status report on oral health 2022 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/team/noncommunicable-diseases/global-status-report-on-oral-health-2022

- Yang J, Zhang Q, Zheng D, Hou F. The economic consequences of oral disorders at global, regional, and national levels [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12628856/

- Ndagire B, Kutesa A, Ssenyonga R, Kiiza HM, Nakanjako D, Rwenyonyi CM. Prevalence, severity, and factors associated with dental caries among school adolescents in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Braz Dent J. 2020;31(2):171–178. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440202002841

- Thorpe S. Oral health issues in the African region: current situation and future perspectives. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(11):8–15. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285909487_Oral_Health_Issues_in_the_African_Region_Current_Situation_and_Future_Perspectives

- Fisher J, Berman R, Buse K, Doll B, Glick M, Metzl J, et al. Achieving oral health for all through public health approaches, interprofessional, and transdisciplinary education. NAM Perspect. 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.31478/202302b

- Amaya A, Medina I, Mazzilli S, D'Arcy J, Cocco N, Van Hout MC, et al. Oral health services in prison settings: a global scoping review of availability, accessibility, and model of delivery. J Community Psychol [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jcop.23081

- Amaya A, Medina I, Mazzilli S, D'Arcy J, Cocco N, Van Hout MC, et al. Oral health services in prison settings: a global scoping review of availability, accessibility, and model of delivery. J Community Psychol [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jcop.23081

- Shomuyiwa DO, Bridge G. Oral health of adolescents in West Africa: prioritizing its social determinants. Glob Health Res Policy. 2023 Jul 19;8:28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-023-00313-2

- Labarca TF, Ortuño D, Neira L, Andrade G, Bravo FJ, Cantarutti CR, et al. Oral health research in the WHO African region between 2011 and 2022: a scoping review [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00220345241272024

- Tanser F, de Oliveira T, Maheu-Giroux M, Bärnighausen T. Concentrated HIV sub-epidemics in generalized epidemic settings. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(2):115–125. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/coh.0000000000000034

- Fiegler-Rudol J, Tysiąc-Miśta M, Kasperczyk J. Evaluating oral health status in incarcerated women: a systematic review. 2025;14(5):1499.. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11900908/

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272790646_The_Theory_of_Planned_Behavior

- Cavanagh C. Healthy adolescent development and the juvenile justice system: challenges and solutions [Internet]. Child Dev Perspect. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdep.12461

- Amaya A, Medina I, Mazzilli S, D'Arcy J, Cocco N, Van Hout MC, et al. Oral health services in prison settings: a global scoping review of availability, accessibility, and model of delivery. J Community Psychol. 2024;52(8):1108–1137 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jcop.23081

- Horowitz C, Lawlor EF. Community approaches to addressing health disparities. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Health Disparities. Challenges and successes in reducing health disparities: workshop summary [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2008 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215366/

- Prosen M, Lukić A. Understanding health and illness among incarcerated persons in the Slovenian correctional system: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2024;362:117467. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117467

- Kumar S, Gopalkrishna P, Syed AK, Sathiyabalan A, et al. The impact of toothbrushing on oral health, gingival recession, and tooth wear: a narrative review. Healthcare [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 15];13(10). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/13/10/1138

- World Health Organization. High 5s: standard operating procedures [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/high-5s-standard-operating-procedures

- Chan WL, Wong HY, Yue R, Duangthip D, Lam P. Dental caries status of children and adolescents in West Africa: a literature review. Healthcare. 2025;13(9):961. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/13/9/961

- Njah JM, Halle-Ekane GE, Atanga SN, Tshimwanga EK, Desembuin F, Muffih PT. From Option B+ to universal “test and treat” in Cameroon: identification and evaluation of district-level factors associated with retention in care. Int J Matern Child Health AIDS. 2023;12(2):e631. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.631

- Agrawal A, Bhat N, Shetty S, Sharda A, Singh K, Chaudhary H. Oral hygiene and periodontal status among detainees in a juvenile detention center, India. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2011;9(3):281–287. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22068185/

- Mulatu Y, Mehdi M, Abaynew Y. Association between oral hygiene knowledge and practices among older dental patients attending private dental clinics in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BDJ Open. 2024;10:59. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41405-024-00243-2

- Aborisade AO, Orikpete EV, Williams AT, Adeyemo YI, Akinshipo AWO, Olajide M, et al. Audit of oral neoplasms in children and young adults in Nigeria. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24:1169. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04958-4

- Erbas Unverdi G, Ozgur B, Gungor HC, Casamassimo PS. Comparison of dmft and behavior rating scores between children with systemic disease and healthy children at the first dental visit. BMC Oral Health. 2024 0;24(1):548. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04285-8

- Chan WL, Wong HY, Yue R, Duangthip D, Lam P. Dental caries status of children and adolescents in West Africa: a literature review. Healthcare. 2025;13(9):961. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13090961

- Shomuyiwa DO, Bridge G. Oral health of adolescents in West Africa: prioritizing its social determinants. Glob Health Res Policy. 2023;8:28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-023-00313-2

- Amaya A, Medina I, Rezaei F, Soleimani P, Bosworth R, Stöver H, et al. Understanding the complexities of oral healthcare delivery in correctional settings: a qualitative exploration of barriers, facilitators, and opportunities. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:3039. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-24447-9

- Human Rights Watch. Children behind bars: the global overuse of detention of children. In: World report 2016 [Internet]. New York: Human Rights Watch; 2015 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2016/country-chapters/africa-americas-asia-europe/central-asia-middle-east/north

- Duangthip D, Chu CH. Challenges in oral hygiene and oral health policy. Front Oral Health. 2020;1:575428. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2020.575428

- Parmar D, Anjali, Verma RK, Sakhamuri S, Dalapati C, Bennadi D, et al. Impact of community-based oral health education programs on dental caries prevalence in school-aged children. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2025;17(Suppl 3):S2373–S2375. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_1448_24